The history of watershed enlightenment in southeast Utah

September 04, 2009

John Strong Newberry

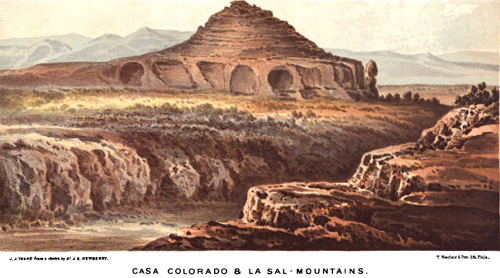

The first professional geographer to explore the watershed of southeast Utah was John Strong Newberry in 1859, and specifically in today's San Juan County. The public would not immediately review Newberry's professional paper due to the outbreak of the Civil War, but the report was eventually published in 1876 and is available here and at Google Books.

Newberry would later become a charter member of the National Academy of Sciences and the First Professor of Geology and Paleontology at Columbia University in New York.

Newberry was the expedition's physician and naturalist and started on horseback from Santa Fe, New Mexico under the command of John N. Macomb of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. The ultimate destination was the Confluence of the Green River and Grand River in what is now Canyonlands National Park.

In Newberry's day the combining flows of these two rivers was the mapmaker's beginning for the Colorado River. That beginning was moved in 1921 to the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains when the state of Colorado requested that the Grand River be formally changed to the Colorado River, which was amicably accepted by all interested parties.

Newberry and McComb never actually gazed upon the joining streams due to lack of time and resources in a rough and arid terrain, but they got close enough to recognize the drainage patterns correctly. They did succeed in naming some of the remaining blank spots for the map making project of the federal government. Newberry coined the name for this greater physiographic province we call the Colorado Plateau.

Newberry described the scientific importance of the Colorado Plateau by saying, "Nowhere on the earth's surface, so far as we know, are the secrets of its structure so fully revealed as here."

Captain John N. McComb, who shared the opinion from the viewpoint of conventional wisdom, declared the landscape as "worthless and impractible."

After this journey Newberry also wrote a paper on the geologic importance of the Abajo Mountains, which is a doming mountain structure caused by intrusive magma, but without an eruption on the surface (volcano). A protégé of Newberry, Grove Karl Gilbert, would study these types of mountains more thouroughly for the Powell Survey in 1875 at the Henry Mountains on the west side of the Colorado River in Wayne County. Gilbert called these mountains of granite, a laccolith. Southeast Utah has four laccolithic mountains and here arranged by descending height: La Sals, Henry's, Abajos, and Navajo.

The learning experience from this scientific expedition that first penetrated the watershed for understanding is: though the entire flow of the Colorado River headwaters consolidate here, the water is basically unattainable. In fact, no community, prehistoric or modern, relied on river water as their permanent source of drinking water. Instead, they use the groundwater and surface water that flows by gravity from the laccothithic mountains to the Colorado River complex of tributary streams.

The modern-day distribution of electricity and energy fuels has changed the natural paradigm somewhat for a few fortunate farmers who lift river water from the Colorado with mechanical pumps to irrigate crops (mostly alfalfa), but that only occurs where the river system is not entrenched in deep canyons. This activity occurs in Grand County where the Dolores River confluence serves as the center point of the radius, and along the San Juan River near Bluff.

The farms of Spanish Valley (Moab) are gravity fed by surface water from the La Sal Mountains and stored at Ken's Lake, which was completed in 1981. The farms near Monticello and Blanding likewise use surface water from the Abajos in reservoirs called Monticello and Recapture.

Additionally, mechanical pumps have allowed the municipalities to increase their yield of water flowing from the laccoliths for growth, but it is important to understand that this particular system has a natural advantage of working without electricity.

The National Surveys

Ten years after Newberry's vist, in 1869, additional gaps of knowledge were filled by John Wesley Powell, who wisely consulted with Newberry beforehand in Washington DC. Powell's famous visit to the Confluence via river boats provided the proper latitude and longitude for the federal map makers.

A geographic reconnasaince of Grand County was not initiated by Powell's river trip, since he approached the Colorado Plateau via the Green River and not the Grand River. In 1875 a team of geographers on horseback, from a federal survey directed by Ferdinand Hayden (who did not participate in the trip), completed the first reconnaissance of Grand County. That team included Henry Gannett, James Gardner and Albert Peale, the later whom the tallest peak of the La Sal Mountains is named after.

The country at the time was inhabited by roving tribes of the Ute Nation who were resistant to visits by foreign people. For example, the early Mormon pioneers in 1855, and the Hayden survey in 1875, did experience serious skirmishes with Ute warriors in Grand and San Juan Counties.

In the late 1870s reservations for the Ute Nation were establshed, which allowed development of southeast Utah to begin. Unfortunately, the dominant white society dscovered mineral wealth in the original reservation lands and consequently the treaties were greatly modified to the disadvantage of the Utes. Ironically, more modern discoveries of oil and gas reserves in the San Juan River basin have since made the Southern Utes one of the richest tribes in the United States.

The Reclamation Era

The national surveys that immediately followed the Civil War were consolidated into one agency by 1879 and called the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Click here for a history of the USGS.

The first director of the Survey was Clarence King, who was replaced by John Wesley Powell in 1881. Much of the focus by the USGS in the West was to provide data and maps for the development of water resources.

In the same year the USGS was formed, Powell's national survey was the first to publish a comprehensive water resource document called Lands of the Arid Region of the United States with a more detailed account of the lands of Utah. The later publications of the USGS were a series called Water Supply Papers (WSP).

For the Colorado River basin one of the first comprehensive Water Supply Papers was written by E. C. La Rue in 1916 (WSP 395), which quantified the annual yield of the river's water supply and also recommended potential damsites, including locations in Grand and San Juan Counties. In 1914, LaRue completed several river trips in Canyonlands by paddlewheel with boatman Tom Wimmer. Click here to read a report (1969) on potential damsites in Grand and San Juan Counties.

In 1917 the upper basin of the Colorado River was mapped in detail and published under the direction of W. H. Herron in WSP 396 (detailed maps of this survey are not yet available on the worldwide web).

From 1921 to 1923 the USGS partnered with Southern California Edison and Utah Power and Light for mapping the whitewater canyons of the Green, Colorado and San Juan Rivers for dams and power plants. They hired local boatmen from southeast Utah, such as Bert Loper and Elwyn Blake. See also Colorado Riverbed Case.

The Water Supply Papers from these river surveys are as follows:

WSP 538 (1924) by Hugh D. Miser: The San Juan Canyon, southeastern Utah, a geographic and hydrographic reconnaissance.

WSP 556 (1925) by E. C. LaRue: Water power and flood control of the Colorado River below Green River, Utah.

WSP 617 (1929) by Robert Follansbee: Upper Colorado River and its utilization.

WSP 618 (1930) by Ralf R. Woolley: The Green River and its utilization.

As it turned out, most of the dams proposed in Grand or San Juan Counties were never built, but Arizona's Glen Canyon Dam and reservoir, Lake Powell, did drown the Colorado River canyons of San Juan County.

Mineral and Petroleum Exploration

The USGS also sent surveys into southeast Utah to assess the potential for mineral and petroleum development. These surveys defined federal lands that would be reserved for the stockpiling of natural resources for national defense, such as the oil shale reserves of the Uinta Basin to the north and the helium reserves of the San Rafael Swell to the west. Prior to, and after World War II, uranium studies too were a dominant focus of many USGS scientists.

Oil and gas exploration occurred as early as 1909 with limited success. Oil and gas traps were typically exhausted before profits materialized. In fact Harry Aurand, a petroleum geologist, always felt the Canyonlands region had more economic potential as a national park than as an oil field, and championed that alternative with the Department of Interior in 1934.

Technology has recently increased the yield of petroleum products in the region, but these increases will have absolutely no effect on resolving our difficult energy problems, and the industry's impacts will actually contribute more harm to our quality of life in the long-term.

The uranium industry is a good example of extraction causing more harm than good. Though uranium ore brought short-term prosperity to southeast Utah after World War II, it must be realized that uranium has always been a scarce mineral in the United States. Its extraction was completely subsidized by the federal government, whose incentive was to stockpile the rare metal at any and all costs for nuclear weapons superiority. In return the community was left with a legacy of human health problems and radioactive pollution that accrued yet another layer of financial burden for the nation's taxpayers to care and clean-up for.

Additionally, oil shale development has been a potential extractive industry for this area and since World War II. If full development arises, it will wreck havoc on the scarce, water supplies of the Colorado River, destroy the surface of this sensitive landscape and, more importantly, direct us from investing the nation's financial resources toward energy development that will contribute to reduced greenhouse gases for our warming atmosphere.

Conclusion

Times have, and have not, changed since Newberry and McComb struggled over tortuous canyons for a view of the mighty Colorado River in 1859. I do think that Newberry had the better attitude of the two. Newberry did not pass instant and condescending judgement on this landscape as did McComb. Newberry had a keen desire to discover what the watershed is and isn't. John Wesley Powell took it to the next level and starting to make plans wrapped around the importance of water. So should we.

As it turns out, the laccolithic mountains have given this community some of the highest quality water in the United States. Since the quantity and quality of water in Colorado River is steadily decreasing, we would be wise to invest our attention toward protecting that which is ours and work hard to avoid the overwhelming contentiousness that prevails around Colorado River management--the contentiousness that Powell predicted would occur as a result of erroneous planning.

Yet it is imperative that we be a good upstream neighbor and share in the responsibility of improving the Colorado River's vibrancy over time.

We also need to appreciate that people come here to experience the quiet wonder of Canyon Country just like Newberry and Powell did. That there is more opportunity here if we preserve the landscape and its culture, than to mangle and demoralize it.

Talk about this article...